Just like magic, standup comedy, sports, and talk shows, effective teaching can look organic and improvised to the naked eye. Experts in those fields, however, know the amount of preparation, precision, and rehearsal that those require. Effective teaching and learning are no different, and actually draws many uncanny parallels. Some elements are highly contextual in the moment; others, calculated, anticipated, and refined. During the school year, there isn’t necessarily time to research, think through, prepare, or organize for innovation — rather, the school year is the time to execute, it’s when we’re in season.

Many people who aren’t in education say things like, “I bet it’s great to have the summers off!” Teachers know that “off” should be in quotes and is always commensurate according to a number of personal factors; often we’re taking classes, continuing certification, traveling w/ students, attending PD, catching up on projects at home, spending time with family, and much more. Summer and other breaks are the offseason; they’re when we can rejuvenate and catch up, and rest itself is relative. Master athletes like LeBron James and Serena Williams know that off-season relaxation and preparation are key, and we as the general public know that. I often wonder why people don’t comment on athletes being lucky to get a “break” like they do to teachers or even any POTUS – for those jobs there are waves of action, sprints within marathons, and some down time is necessary for both. During said down time, without the crowd, without the class, we fine-tune, strengthen, learn, and much more. We don’t get aggravated at cherries for not being available year-round because that’s not how it works — teachers are the cherries. We need time. We, too, have a season.

High-performing athletes, high-performing teachers, and the farmers of the aforementioned cherries also know to trust certain processes, and that precise practice over time equals achievement. We must be measured, intentional, and determined. If they skip a day at the gym, or the field doesn’t get fertilized on time, they expect to feel it as a consequence. Equally, if we skip a day of planning or a critical training, we can expect to get behind. None of these jobs have a silver bullet, either — if I do X, I will get Y result. Progress will take time and effort; there is no shortcut. Thinking of shifting to proficiency? Get reading, familiarize yourself with indicators and frameworks, get processing. Thinking of wandering away from a textbook and using stories, or TCI/TPR, etc.? Watch YouTube videos, read blog posts, gather, gather, gather. We’re about to be in-season, and if Serena isn’t changing her backhand AND her forehand AND her serve AND her footwork right before tournaments rev back up, then it isn’t wise for us to change-up eight different things at the same time and expect them to go well, simultaneously. We can start with a solid, do-able foundation of goals, and then work on those things over time. Next year, we refine, scrap, and/or add a couple more, and soon, the systems will all be working with and for each other. When it comes to in-season, school-year goals, consider depth, not breadth, and don’t forget to factor in time and life.

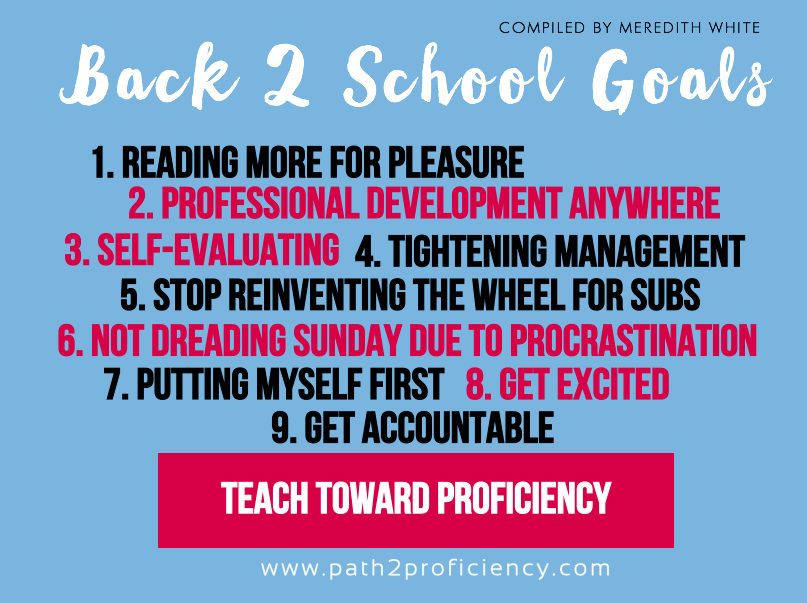

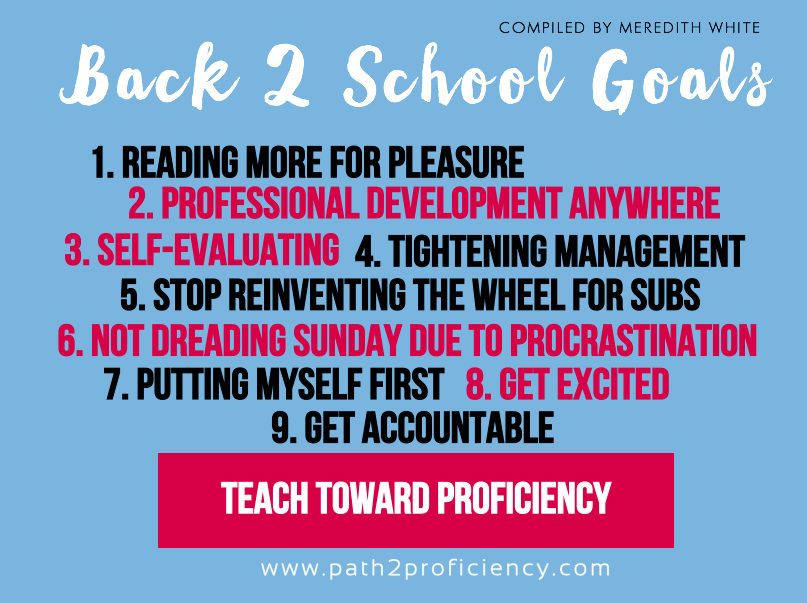

Here are some of my own past goals and how I’ve maintained them:

1. Reading more for pleasure

I joined Book of the Month Club and it was a great investment – instead of only watching TV at night, I now switch it up and read for a little while, right before bed.

2. Professional development anywhere

I wondered what all the buzz about #langchat was, so I joined Twitter (for professional use only) a few years ago. Every Thursday at 8pm (eastern), or 10am on Saturdays, I logged in, searched #langchat, and watched questions and answers populate. There’s a different topic each week, the same for both days, and the moderators organize each topic into five individual questions, the ‘discussion’ lasting about eight minutes each. The questions segue into each other and are designed to target a varied audience in terms of pedagogies, experience levels, demographics of students, etc.

3. Tightening management

I got into the habit of video recording class (and my teaching) twice a week. Yep. Gulp. Twice a week, every week. And then, I watched it back. Gulp #2. Of course, before doing that, you may want to put on your pajamas, have your feet up, and get a libation of choice. Watching ourselves is never easy, but I’ve never grown so much in one year as I did that year. Now, I record class all the time and use it for absent students (especially critical input!), other teachers to see certain activities, self-reflection, EdPuzzle.com homework videos, and more. That one resource can fuel a LOT – don’t be afraid to record yourself and see what’s really going on in your classroom. (PS We were smiling and laughing way more than I realized, and after many hard days, I had to really savor seeing those moments documented, because it didn’t feel like it, at all.)

4. Self-evaluating

The TELL framework and subsequent self-evaluation tools are invaluable here – seriously, an entire framework about effective, model language teaching. It won’t happen like this every day, all day, all season (remember, it’s not supposed to!), but it’s a great start and the indicators are fabulous. Developed by language teachers, for language teachers.

5. Stop reinventing the wheel for subs

5. Stop reinventing the wheel for subs

Whether it’s buying from TeachersPayTeachers vendors, using OER, whatever – find a framework of tasks that works for any level at any point in the year. “Using your current, ___, use ___ to create ____ and turn in via ____,” etc. I like to find stories and other stand-alone reading activities that I can purchase, print, and leave for my sub with this frame holding the instructions on my desk AND at each group of desks. I do this once at the beginning of the year and don’t have to worry about updating my emergency sub plans, just the rosters, and can then plan for any sub I’ve scheduled for. I’m happy, my dept. head and admin. are very happy, and it’s OK if life happens and I have to be absent unexpectedly.

6. Not dreading Sunday due to procrastination

Man, this one was tough. REALLY tough. But, finally, finally, wonderfully, I don’t hate Sundays, and weekends aren’t necessarily a time to catch up; they’re a time to weekend (we can make ‘to weekend’ an infinitive, can’t we?). In staying merely a week or two completely ahead, within a pacing guide, of course, and putting in a little concentrated time on Saturday mornings (or wherever works for you), I’ve saved myself many, many evenings and late nights of work. Also, learning about myself that I’m a morning person has helped immensely. I would rather get to bed early knowing I can get up at 4, shower, put on my robe while my hair air dries, grab a cup of coffee (had the maker programmed to turn on also at 4), and snuggle back into bed with my computer to look over a few things for the day/week/whatever, in the early-morning quiet than be up until 10, 11, etc. Nope – good for some, not for me. I learned this by trying different routines for a couple of weeks – morning gym, afternoon gym, early morning work, staying up later – that was my conclusion. Mornings and some concerted time every other Saturday have made my life much less stressful. Also, I recommend dividing out your planning period by day and time chunk. For me, it’s easier to prioritize that way.

7. Putting myself first

I get a gel manicure every two or three weeks, and massages from time to time. Gel nail polish is amazing because it doesn’t screw up when you reach for your wallet or keys, and massages help my legs and back stay relaxed after standing all day, every day. I make these appointments when time and money allow, and purposefully at 4pm or a little before; then I have a reason to leave and enjoy something that’s only for me. Also, it’s a luxury, and it isn’t anyone else’s business – if something comes up, I simply say, “Shoot, I have an appointment. How’s [other day]?” and I don’t feel badly. Be careful in when feeling the need to explain or apologize for how you use your time. It would be too easy to reschedule and accommodate something or someone else instead of me, when I already had those plans made, and I personally now save those accommodations for emergencies only. (Same goes for e-mail!)

8. Get excited

Along the lines of number seven, get excited about something. At the time, my husband and I were new to a city, and we made it a mission to try several highly-reputed restaurants. I made the reservations early, so that we couldn’t get ‘busy‘ and cancel, and then we got excited about it. Something to look forward to is huge. My current department goes for margaritas and chitchat once a month, and I try to have friends over to just cook and hang out. Simple things like free events at the botanical gardens, a babysitter for the evening, a movie at one of those places that serves food and drinks – whatever it is, get something to look forward to. In October and February, seven and eight in this list are what sustain me, big time.

9. Get accountable

Find someone, preferably another WL teacher, with whom you can be vulnerable and honest — tell them your goals for the year, and set yourself a phone reminder or the like to chat or catch up about said goals, both of you. I can always trust Paul Jennemann and we’ll drop each other a text to check in, from 300 miles away. Keep it simple, but keep it purposeful. Vent, share, move forward. Once I’ve prioritized, I’ll post my own 2017-18 goals below in the comments so that you all can keep me accountable!

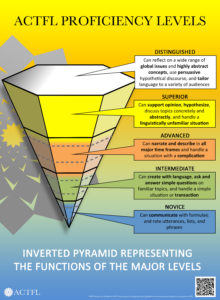

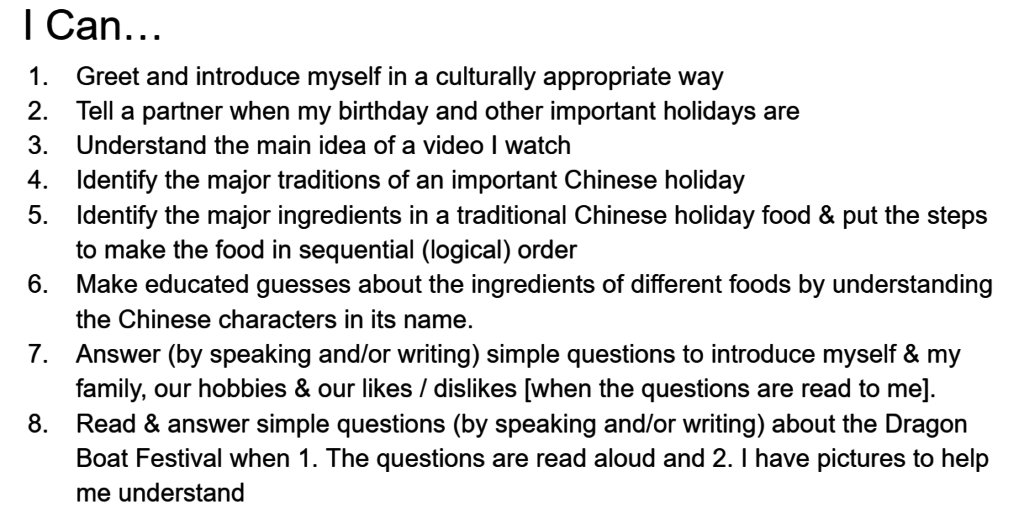

10. Teach toward proficiency

It’s been a long, wonderful journey, and I’m excited to continue it this year with some specific foci. It starts with versing one’s self on proficiency, and then introducing it to students. Teach them the jargon, keep yourself on target, and it takes on a life of its own.

Each time I’ve started a school year either overzealous or without a plan at all, I’ve burnt out early and been disappointed in what didn’t happen. Rather, I should’ve been seeing and celebrating the victories. At the same time, also realize that some things are unavoidable. Farmers aren’t getting 500% their usual rain to then be baffled as to why there wasn’t a bumper crop — it just wasn’t meant to be. Tiger Woods is still coming back from several injuries that are keeping him from peak performance and knows he won’t be ranked #1 right now. Serena herself is starting a family and making plans that allow herself rest and quality time before returning to competitive tennis. With a class of 40+, emergencies, family circumstances, unforeseen financial issues, or over-committing yourself and realizing too late, give yourself grace to have the best season you can, learn from it, and move on. Do not compare yourself, and do not look at everyone else’s highlight reel while only seeing your bloopers. Just like the rain, or missing Wimbledon or the NBA Finals, it wasn’t meant to be that season, and that’s OK. Seasons come and go. We wait for it to come back around, we plant the seeds, we train the team, we prep the lessons, we weather the storm(s), and we give it another shot.

Here’s to a GREAT 2017-18 school year!

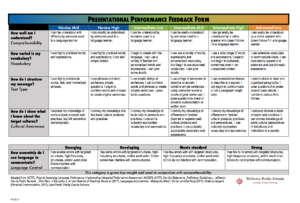

I set to work and created a seventeen-page rubric. Yes, you read correctly, seventeen pages! The series contained a separate rubric for each performance mode and each targeted sub level of proficiency for presentational writing and speaking. I hadn’t even gotten to interpersonal yet. Before writing anything, I reread several ACTFL publications, looked over the many pages I’d highlighted in Helena Curtain and Carol Ann Dahlberg’s

I set to work and created a seventeen-page rubric. Yes, you read correctly, seventeen pages! The series contained a separate rubric for each performance mode and each targeted sub level of proficiency for presentational writing and speaking. I hadn’t even gotten to interpersonal yet. Before writing anything, I reread several ACTFL publications, looked over the many pages I’d highlighted in Helena Curtain and Carol Ann Dahlberg’s